Publications for download

To request copies of my publications, please contact me thru ResearchGate:

RECENT PUBLICATIONS

Coronado-Franco, K., Tedesco, P.A., Kolmann, M.A., Borstein, S., Evans, K.O., Correa, S.B. Accepted. Feeding habits influence species habitat associations at the landscape scale. Journal of Biogeography.

de Brito, V., Betancur-R, R., Burns, M.D., Buser, T.J., Conway, K.W., Fontenelle, J.P., Kolmann, M.A., McCraney, W.T., Thacker, C.E. and Bloom, D.D. 2022. Patterns of Phenotypic Evolution Associated with Marine/Freshwater Transitions in Fishes. Integrative & Comparative Biology. 62(2): 406-423.

Kolmann, M.A., Marquez, F.P.L., Dean, M.N., Weaver, J., Fontenelle, J.P., Lovejoy, N.R. 2022. Ecological and phenotypic diversification after a continental invasion in Neotropical freshwater stingrays. Integrative & Comparative Biology. 62: 424–440.

Fontenelle, J.P., Lovejoy, N.R., Kolmann, M.A., Marques, F.P.L. 2021. Molecular phylogeny for the Neotropical Freshwater Stingrays (Myliobatiformes: Potamotrygoninae) reveals limitations of traditional taxonomy. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 134(2): 381-401.

Fontenelle, J.P., Marques, F.P.L., Kolmann, M.A., Lovejoy, N.R. 2021. Biogeography of the Neotropical freshwater stingrays (Myliobatiformes: Potamotrygoninae) reveals effects of continent-scale paleogeographic change and drainage evolution. Journal of Biogeography.

Kolmann, M.A. & Kalacska, M., Lucanus, O., Sousa, L., Wainwright, D., Arroyo-Mora, P., Andrade, M. 2021. Hyperspectral data can distinguish among Neotropical fishes: a new method for screening biodiversity. Scientific Reports.

Kolmann, M.A., Hughes, L., Hernandez, L.P., Arcila, D., Betancur, R., Sabaj, M., López-Fernández, H., Ortí, G. 2021. Phylogenomics of piranhas and pacus (Serrasalmidae) reveal how convergent diets obfuscate morphological taxonomy. Systematic Biology.

Kolmann, M.A., Peixoto, T., Pfeiffenberger, J., Summers, A.P., Donatelli, C.M. 2020. Swimming and defense - competing needs across ontogeny in armored fishes (Agonidae). Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 169(17): 1-11.

Kolmann, M.A., Ng, J., Burns, M., Lovejoy, N.R., Bloom, D.D. 2020. Body shape evolution across habitat transitions in marine and freshwater needlefishes. Ecology & Evolution.

Bloom, D.D., Kolmann, M.A., Foster, K., Watrous, H. 2020. Mode of miniaturization influences body shape evolution in New World anchovies (Engraulidae). Journal of Fish Biology. 96: 194– 201.

Kolmann, M.A., Urban, P., Summers, A.P. 2020. Structure and function of the armored keel in piranhas, pacus, and their allies. Anatomical Record. (Note: this manuscript was accepted in 2018, but part of a special issue collated in 2020)

Kolmann, M.A., Cohen, K, Bemis, K, Summers, AP, Irish, F, Hernandez, LP. 2019. Tooth and consequences: heterodonty and dental replacement in piranhas and pacus (Serrasalmidae). Evolution & Development.

Buser, T., Finnegan, D., Summers, A.P., Kolmann, M.A. 2019. Have niche, will travel. Quantifying diet and ecomorphology reveals niche conservatism in cottoids. Integrative Organismal Biology.

Rutledge, K., Summers, A.P., Kolmann, M.A. 2019. Killing them softly: ontogeny of jaw stiffness in a durophagous freshwater stingray. Journal of Morphology.

There are many ways to be a scale-feeding fish.

Although rare within the context of 30 000 species of

extant fishes, scale-feeding as an ecological strategy has evolved repeatedly across the teleost tree of life. Scale-feeding (lepidophagous) fishes are diverse in terms of their ecology, behaviour, and specialized morphologies for grazing on scales and mucus of sympatric species. Despite this diversity, the underlying ontogenetic changes in functional and biomechanical properties of associated feeding morphologies in lepidophagous fishes are less understood. We examined the ontogeny of feeding mechanics in two evolutionary lineages of scale-feeding fishes: Roeboides, a characin, and Catoprion, a piranha. We compare these two scale-feeding taxa with their nearest, non-lepidophagous taxa to identify traits held in common among scale-feeding fishes. We use a combination of micro-computed tomography scanning and iodine staining to measure biomechanical predictors of feeding behaviour such as tooth shape, jaw lever mechanics and jaw musculature. We recover a stark contrast between the feeding morphology of scale-feeding and non-scale-feeding taxa, with lepidophagous fishes displaying some paedomorphic characters through to adulthood. Few traits are shared between lepidophagous characins and piranhas, except for their highly-modified, stout dentition. Given such variability in development, morphology and behaviour, ecological diversity within lepidophagous fishes has been underestimated. Read it here,

Kolmann, M.A., Huie, J., Evans, K., Summers, A.P. 2018. Specialized specialists and the narrow niche fallacy: a tale of scale-eating fishes. Royal Society Open Science.

What sharks live in Guyana?

A fundamental challenge for both sustainable fisheries and biodiversity protection in the Neotropics is the accurate determination of species identity. The biodiversity of the coastal sharks of Guyana is poorly understood, but these species are subject to both artisanal fishing as well as harvesting by industrialized offshore fleets. To determine what species of sharks are frequently caught and consumed along the coastline of Guyana, we used DNA barcoding to identify market specimens. We sequenced the mitochondrial co1 gene for 132 samples collected from six markets, and compared our sequences to those available in the Barcode of Life Database (BOLD) and GenBank. Nearly 30% of the total sample diversity was represented by two species of Hammerhead Sharks (Sphyrna mokarran and S. lewini), both listed as Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Other significant portions of the samples included Sharpnose Sharks (23% - Rhizoprionodon spp.), considered Vulnerable in Brazilian waters due to unregulated gillnet fisheries, and the Smalltail Shark (17% - Carcharhinus porosus). We found that barcoding provides efficient and accurate identification of market specimens in Guyana, making this study the first in over thirty years to address Guyana’s coastal shark biodiversity.

Kolmann, M.A., Elbassiouny, A.A., Liverpool, E.A., & Lovejoy, N.R. 2017. DNA barcoding reveals the diversity of sharks in Guyana coastal markets. Neotropical Ichthyology. 15(4).

Stingrays chew: shearing jaw motions help to eat tough insect prey

Freshwater stingrays are found in South American river basins and feed on a diverse array of prey. Many of these species specialize on a single kind of prey, be they fish, crustaceans, snails, or even aquatic insect larvae. But not all of these prey are created equal – some prey are harder, softer, or tougher than others. Insectivorous freshwater stingrays are the only elasmobranchs (sharks and rays) to feed on insects – which are difficult to eat and digest due to high amounts of chitin in their exoskeletons, a remarkably complex and tough material. Other vertebrates, namely mammals like shrews, bats, and tenrecs also eat insects and they use complex jaw motions – chewing – to shred chitin to allow digestive juices to breakdown prey. Stingrays can protrude their jaws away from their skull as well as protrude these jaws laterally, to the left or right. Using high-speed videography we determined that freshwater stingrays (Potamotrygon) do actually chew their food – just like mammals. We also found that these stingrays lift their disk to suck prey underneath the body – thereby capturing food with their pectoral fin ‘limbs.’

Kolmann, M.A., Welch, K.C., Summers, A.P., & Lovejoy, N.R. (2016). Always chew your food: freshwater stingrays use mastication to process tough insect prey. Proceedings of the Royal Society: Part B. 283: 20161392.

The evolution of mitochondrial genomes in Neotropical electric fishes

A new paper by my labmate, Ahmed Elbassiouny, on which I am a coauthor! Really interesting look at the evolution of mitochondrial genomes in fishes which use electricity to navigate, communicate, and sometimes even for defense!

Elbassiouny, A.A., Schott, R.K., Waddell, J.C., Kolmann, M.A., Lehmberg, E.S., Van Nynatten, A., Crampton, W.G., Chang, B.S. and Lovejoy, N.R., 2016. Mitochondrial genomes of the South American electric knifefishes (Order Gymnotiformes). Mitochondrial DNA Part B, 1: 401-403.

Redundant function across stingray jaw morphology

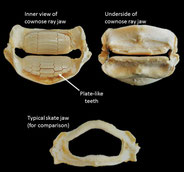

All stingrays in the family Myliobatidae eat hard-shelled prey, be it crabs, snails, or clams. Just as there are differences in diet between these rays, there are different jaw shapes - presumably these two phenomena are related (ecomorphology); afterall, form follows function. We were interested in if different jaw shapes conferred a performance advantage for consuming specific hard prey. We made replica metal jaws for each ray species, rendered from computed tomography scans, and crushed live mollusks as well as 3D printed shells with these fabricated jaws. We found little difference in crushing performance between jaw shapes, suggesting that disparate morphologies are equally well-suited for crushing many kinds of shelled prey. This redundancy of function is despite prey exhibiting varying resiliency to crushing; regarding either the amount of energy invested (work) or the raw amount of force (load) required to fracturing the shells.

Kolmann, M.A., Crofts, S.B., Dean, M.N., Summers, A.P., & Lovejoy, N.R. (2015). Morphology does not predict performance: jaw curvature and prey crushing in durophagous stingrays. Journal of Experimental Biology. 218: 3941-3949.

A tendon-pulley system harnesses jaw muscle forces in stingrays

We find that positive allometric growth of the primary feeding musculature, and not favorable lever mechanics drive increases in feeding performance (i.e. bite force) in juvenile cownose rays - in other words, juvenile rays have greater than expected ability to consume hard prey than we would expect given their smaller size. This is imperative for animals that eat durable prey, in this case, bivalves. Cownose rays use a Type-1 pulley system that arises from a tendon-sesamoid-muscle complex in order to reroute and therefore amplify muscle forces across the tooth surface - making them effective molluscivores.

Oh, and this is one of the only studies to analyze feeding performance in a stingray!

Kolmann, M.A., Huber, D.R., Motta, P.J., & Grubbs, R.D. (2015). Feeding biomechanics of the cownose ray, Rhinoptera bonasus, over ontogeny. Journal of Anatomy. 227(3): 341-351.

Decoupling of the jaws from the skull & novel muscle function

My abbreviated, functional review of feeding anatomy in stingrays. It poses functional hypotheses regarding general function of feeding structures (mostly muscles), with particular focus on the anatomical differences between durophagous and non-durophagous stingrays. We find that muscular complexity increases in general from ratfishes to sharks to batoids, possibly due to de-coupling of the jaws from the cranium (jaw suspension).

Kolmann, M.A., Huber, D.R., Dean, M.N., & Grubbs, R.D. (2014). Myological variability in a decoupled skeletal system: Batoid cranial anatomy. Journal of Morphology. 275(8): 862-881.

Scaling of feeding performance drives early access to "hard" prey

My study of feeding performance over ontogeny in horn sharks. We found that muscular hypertrophy drives positive allometry of bite force generation in these sharks. We also demonstrate that these functional gains in feeding performance allow horn sharks to prey on a large size range of sea urchins (a primary prey item in California) from a relatively small size.

Kolmann, M.A., & Huber, D.R. (2009). Scaling of feeding biomechanics in the horn shark Heterodontus francisci: ontogenetic constraints on durophagy. Zoology. 112(5): 351-361.

Kolmann Lab

Form.Function.Evolution

Kolmann Lab

Form.Function.Evolution